by Moriah Thomas

Sergeant Carl Mitcham – buzz-cut blond, blue-eyed, tall – checks over the supplies in the back of his police car in the parking lot of the nondescript police station. First aid materials. A surgical gown. A stuffed animal for the kids. An ax.

As the sun sets, he is expecting another ordinary patrol shift. Tonight, he heads to the Athens homeless communities. From his time in the air force, like his dad, as a mental health technician to the Athens police department’s Crisis Unit– Mitcham has extensive experience with mental health. For years now, he has been at the forefront of Athens mental health for the homeless. And at only thirty years old.

Some of the people on the streets even affectionately call him ‘Sarge” on his night shift patrols and the local “front line” homeless shelter welcomes him in their doors even past operating hours. Despite efforts to stem homelessness in Athens, it has risen 20% from last year – something Mitcham notices during his check-ins with communities like those off of Dakota Drive.

After hitting the road, he parks on a dirt shoulder between the busy, bright highway and the dark, quiet woods. The area was supposed to be a new subdivision, but the stock market crash of ’08 halted the build. But not before some of the infrastructure was built, even a bridge with an inscription dating is to 2008. The perfect place for those who have nowhere else to go.

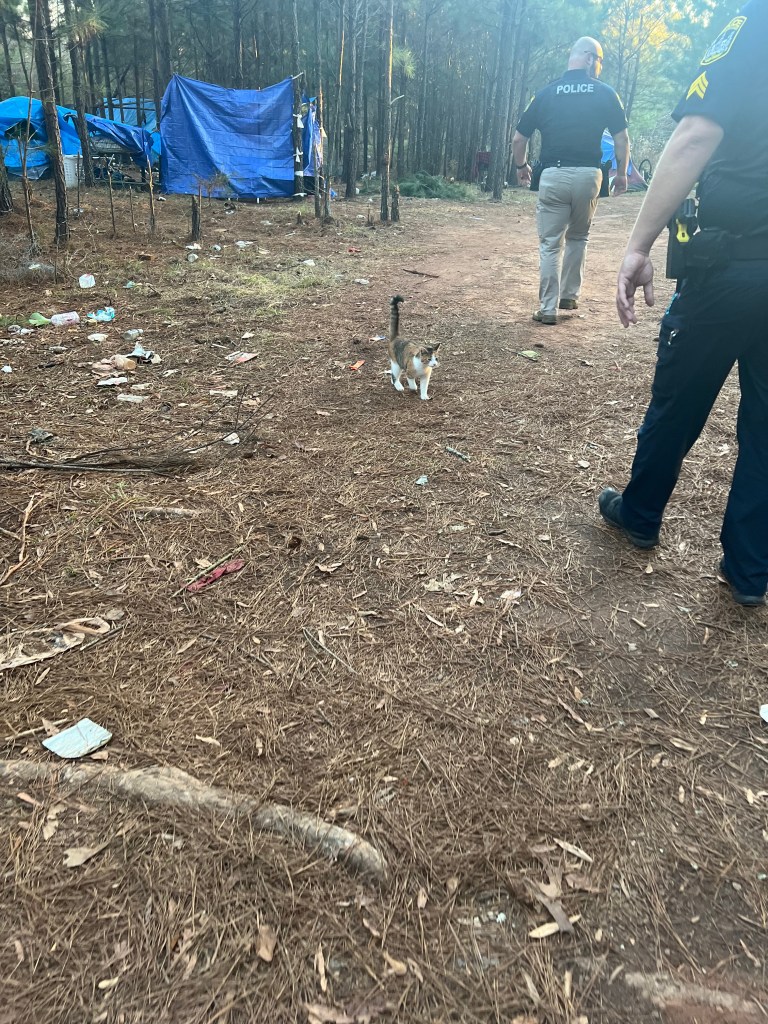

Despite Mitcham’s light personality and ready smile, he knows that this job is dangerous both physically and mentally. He never knows what the night is going to bring. So he uses the buddy system – whether that’s having a fellow officer walk through these physical woods with him or discussing trauma coping techniques with his clinician partner. As he and Officer Doster make their way into the trees, aside from the flashlights and lights from the drone scout – buzzing with red, green, red, green above – it’s pitch black. Not unlike a few years ago when Mitcham was the one piloting the drone while two other officers were on a routine check-in at this very encampment. They witnessed a drug deal and chased the dealer through the woods until they tased him down after he tried to choke one of the officers.

Now he enters those same woods again. What will he face this time?

The first thing he smells is urine, then weed and a campfire. Mitcham makes his way from tent to tent. He can’t hear the sounds of the highway anymore. A woman in a wheelchair, her leg amputated, sits with her back turned. She doesn’t look up from her coloring book, which has a beaded handle.

“How are you doing tonight, ‘mam?”

“Fine.”

“Got your coloring book there? Everybody’s gotta’ have their outlet.”

By this time a calico cat picked up on the fact that Mitcham is not a dog person. As if it can sense that it wouldn’t be the first time Mitcham has taken a stray home, it follows him as he cuts off the dirt path and into the brambles and trees. Doster has caught up to a young woman named Danielle. She’s frazzled and admits she is on two uppers. Her short red hair stands out when the flashlight shines across her. She recently left rehab and is using again. Mitcham has one hand in his pocket as he listens to her tell her story. The cat meanders around their feet.

“I just wish that I would have went to a meeting, talk to my sponsor,” she said.

Mitcham takes his hand out of his pocket, grab his notepad and pen to write down an address to a mental health clinic.

He looks her in the eyes, “I hate to put it in this blunt of a term, but relapse is a part of recover, right?”

“Ya.”

“I appreciate you talking with me. I think we’ve had a good conversation. If you don’t mind me asking – what do you use?”

“Um, mostly fentanyl, but I did some uppers today and [it] kind of f-ed me up.”

“Is that normal or…?”

“I mean, uh, ya, that’s – I prefer downers ‘cause I’m already really mental health and anxious. So when I do uppers, it sets me off. It makes me a really anxious person and uncomfortable.”

“I know, obviously you want to try to pull yourself out of this. You’ve tried, sounds like a couple of times before. Keep trying.”

He offers to give her a ride and tells her to call if she needs them. The cat leads everyone out of the thick of the woods and back onto the path, like a little guardian.

This isn’t the first time Mitcham has deescalated a situation with an unhoused person just by listening to them. Before he was a Sergeant, his clinician partner Drew and him were called to a scene. When they arrived, a group of officers stood near a single man, unhoused. This man had been the subject of many calls, but Mitcham wasn’t frustrated. The man, however, was very frustrated. He was yelling at the other officers. Why was no one listening to him? His eyes searched for someone in the crowd. When Mitcham approached him, he stopped yelling.

“Mitch, Mitch! I’m so glad you’re here. I need your help.”

He stood up from the ground. He had soiled himself and was covered in filth. Mitcham walked up to him and hugged him. Mitcham was able to get him in the ambulance and follow him to the hospital – where the Sergeant is well-known. He didn’t have to follow the ambulance, but he wanted to do what is called a warm handoff – making sure that the man’s situation is explained completely.

Mitcham did not follow up. He never does when he drops someone off at a hospital. Not that he’s heartless, he just talked enough with Drew to know how to set boundaries so that he can continue to do his job. So that he can continue to help the people living in tents in the woods tonight. As he walks down a large mud road to continue his patrol, the cat still follows. The night isn’t finished yet.

Fresh tire tracks lead to a large pile of trash. He knows this isn’t from the homeless. People drive here to dump their trash. Doster spots the cardboard box first. The flashlight trains onto it and stops. The top of a head, caked with mud, is just visible. Doster doesn’t move. Well, Mitcham thinks, I must have enough trauma, why not add a little more. So he picks his way, slowly, through the trash. He’s been through this before.

When he served on the Crisis Unit, he was immediately partnered with mental health clinician Michael Drew. As partners who work twelve-hour shifts together, it’s important to be on the same page. Mitcham and Drew built a bond of respect and friendship. Mitcham’s genuine care for those with mental illnesses impressed Drew, and his childlike spirit helped them to decompress after work. Mitcham still vividly remembers one of their night shifts when they were called to a train track. A homeless man had been hit by a train. Drew had gone to find the train since they take a while to stop. Mitcham was looking for the body. The head had been severed. They had just spoken to the man recently. He had all his belongings with him, so it couldn’t be suicide, right? Why did the body have so little damage? How had he not heard the train coming? Mitcham would never find out. Instead of answers, he’s only left with are the images of the man’s cauterized wounds and decapitated head.

But he’s not at those train tracks anymore. He’s on the mud road making his way towards another bodyless head.

He makes his way slowly over the trash, towards the cardboard box that just fits the head inside. He uses his flashlight to move part of the box aside. The air is still and not a sound can be heard as an eternity passes before more of the head is visible. A face. Dirty and mangled — and plastic. A mannequin’s head.

The relief in the night air is instant and nearly overwhelming. It’s not real. The head isn’t real this time.

There’s nothing left to do but make his way back to his patrol car. The cat follows as he heads back through the dark woods. Follows him until he can see the highway, the lights again.

Once he’s back in his SUV, he drives to a nearby QT. He eats his late “lunch” on the hood of another officer’s car. He has to take out two of his false front teeth to eat the pretzel and jokes that he’ll sometimes take them out to make the homeless feel like more comfortable, like he’s one of them.

Despite hard nights like these, day shifts wouldn’t be as fulfilling for him. Even though part of his job is recovering decapitated heads and never finding out why; he enjoys the part of his job where he gets to be the person someone looks for in a crowd.

The murder of nursing student Laken Riley earlier this year has prompted somewhat of a backlash from the community to step up safety measures and placed increased pressure on law enforcements. Mitcham tries to balance his compassion for the unhoused with his duty to the safety of the community. He advocates for more time when encampments on private property are broken up and patiently listens to those who need an ear. All while trying to avoid burn out with his own mental health.

Mitcham is a man of compatible contrasts. Like his extra magazine clip that’s painted pink with a sprinkles design. His jovial spirit has allowed him to work in one of the most dangerous jobs in Athens for years. Like tonight as he washes his meal down with an extra, extra-large version of a Monster drink since, because, as he says lightly, “We [cops] don’t live long. Fifty or sixty. I’m not going for a record.”